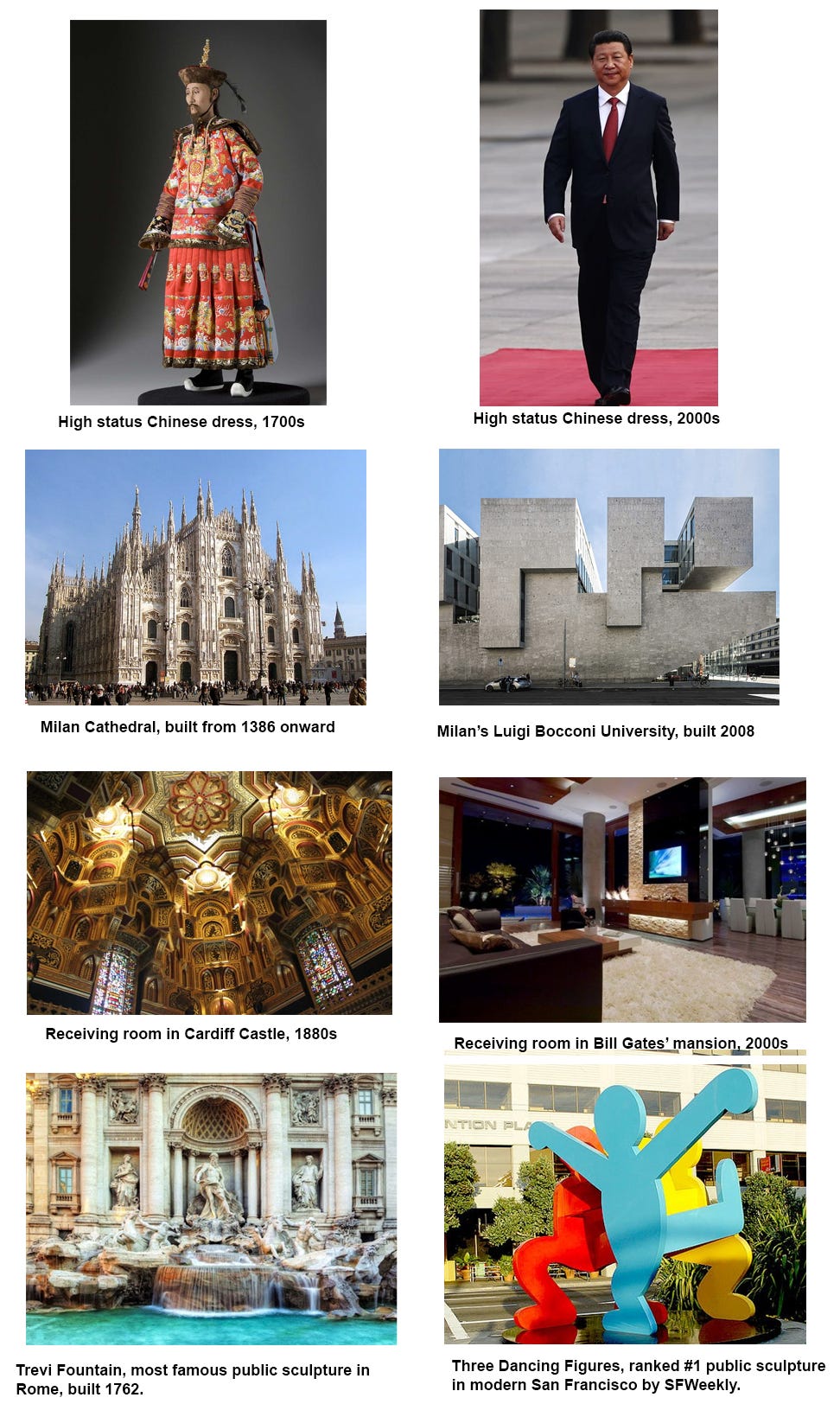

“Why does everything seem so ugly nowadays?” “When did we stop having good taste?” From AI slop to endless movie sequels, sweatpants, and grey concrete buildings, a thought seems to be crystallizing in many circles: our collective aesthetic environment is in decline.

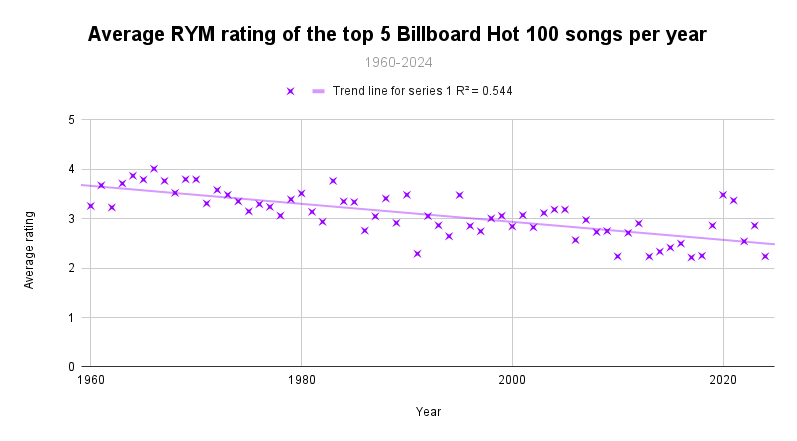

But is there any substance to this claim? For example, is popular music really getting worse? Is “back in my days, we used to have real music on the radio” just boomer nostalgia, or an actual phenomenon?

To explore this, we can turn towards the Billboard Year-End Hot 100, the chart that ranks the best-performing singles of the United States. That’s the “popular” aspect.

I used Rate Your Music (RYM) as a proxy for “artistic value”. RYM is a sprawling, long-running database and community where listeners rate and review albums, singles, and even films and video games. Crucially, the site actively moderates ratings, removes obvious spam, and ensures the averages reflect a serious consensus. For cultural data, it’s about as close to a reliable crowd-sourced record of taste as we have.

So, I took the top 5 most popular songs from the Billboard Hot 100 each year from 1960 to 2024 and looked up their score on Rate Your Music. This gave me an average rating for each year.

Here is a little table comparing 1966, the greatest year on record, with 2017, the worst year:

| Top 5 Billboard Hot 100 songs (1966) | RYM rating | Top 5 Billboard Hot 100 songs (2017) | RYM rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Mamas and the Papas - California Dreamin’ | 4.25 | Ed Sheeran - Shape of You | 1.43 |

| ? and The Mysterians - 96 Tears | 3.87 | Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee - Despacito | 1.77 |

| Jimmy Ruffin - What Becomes of the Brokenhearted | 3.93 | Bruno Mars - That’s What I Like | 2.93 |

| The Monkees - Last Train to Clarksville | 3.85 | Kendrick Lamar - Humble | 3.36 |

| Four Tops - Reach Out I’ll Be There | 4.14 | The Chainsmokers & Coldplay - Something Just Like This | 1.65 |

Yes, it’s only the top five songs (I didn’t have the resources to go further). And yes, you can nitpick the sample: maybe everyone on RYM is old and hates new music. But the data (and my own experience on the site) suggest otherwise. The majority of users are in the 18–24 range, and they clearly don’t hate pop. Take 2020, for instance: its average score is 3.48 (right up there with the 1970s) and its biggest hits came from The Weeknd, Post Malone, Roddy Ricch, and Dua Lipa.

Ok, maybe you don’t still trust Rate Your Music, that’s fine. There are plenty of other signs.

- In a large-scale analysis of nearly one million songs, Serrà et al. (2012) found that popular music has become increasingly homogenized over time, with transitions between melodies and timbres growing more repetitive and predictable from 1955 to 2010.

- van den Bosch et al. (2024), showed that “song lyrics have become simpler and more repetitive over the last five decades”.

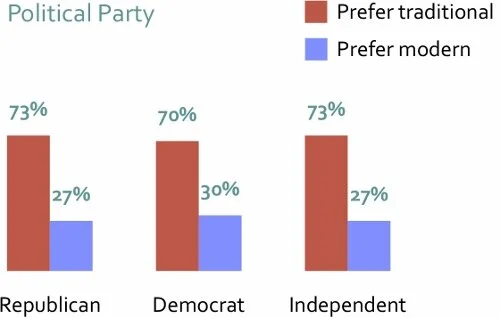

- A 2020 National Art Survey conducted by The Harris Poll showed that 72% of respondents prefer more traditional, ornamented architectural styles over Modernist styles (consistent across many different dimensions).

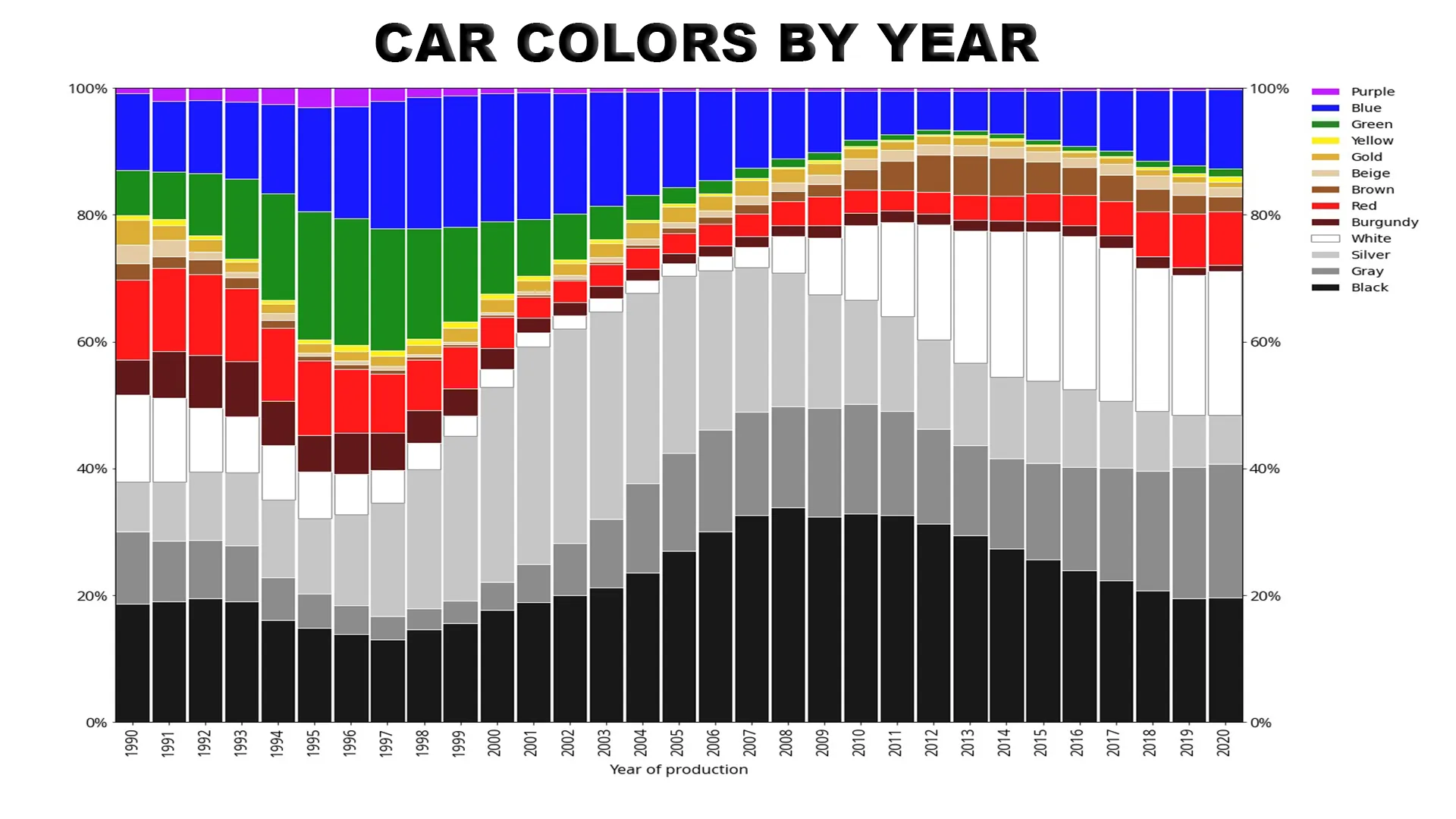

- In 1995, grey, white, and black represented roughly 40% of the car colors sold in the US. In 2020, they represented more than 70%.

- In the mid 2010s, company logos started all looking like each other, a phenomenon known as blanding.

- Sad beige is now the prevalent aesthetic in many interiors and outfits.

- Everything else. From Scott Alexander:

Where are all the colors, the fun, the beauty? Are we condemned to a grey, formulaic, homogenized world? I will argue that beauty is not a luxury, but a fundamental pillar of a healthy mind and a flourishing society. Beauty provides the deep meaning that makes life truly worth living, and we should care about it.

So, what can we do? First, we need to clear one major objection: the one that taste is purely subjective. Of course, there is some truth to it (we obviously don’t all like the same things), but it’s a rather unhelpful statement. Taste has a mechanism, with roots in evolutionary biology and cognitive science. As a species we tend to rally around things that we find more beautiful/pleasant than others. And this is a good place to start if we want to know how to make more of those.

Thus, I want to share a new way of thinking about taste. A framework that ties together how we sense, process, and value art. By understanding how it works, we can learn to sharpen it, expand it, and create art that resonates more.

The layers of taste

In this “unified” theory, taste is a layered and relational process. From raw sensory data to our eventual judgment/appreciation, multiple factors play a role.

Just as important, these layers are cumulative. Once a new influence is absorbed, it can’t simply be erased, and reshapes every later encounter. For instance, each new piece you hear in a genre subtly changes how you hear the next. Prior knowledge and exposure become part of the lens through which all future experiences are filtered.

The factors broadly follow this order:

- Sensory foundations: All taste begins with perception. Our sensory organs set the boundaries of what we can experience, filtering color, sound, texture, and form. Differences in sensitivity or clarity can alter how beauty is felt.

- Evolutionary preferences: Evolution has tuned us to favor signals of safety and vitality: harmony over noise, lush landscapes over deserts, etc.

- Neural processing: The brain rewards what it can encode easily. Orderly, coherent patterns trigger pleasure through neural fluency, dissonance or chaos feel jarring.

- Cognitive interpretation: We process data through prediction, pattern-solving, and conceptual integration that transforms confusion into understanding.

- Emotional resonance: Art can evoke and organize feelings, creating coherent emotional experiences even from “negative” content.

- Informational context: Knowledge and framing reshape perception. Understanding the intent, history, or symbolism behind a work can unlock layers that were invisible before.

- Social and status dynamics: Taste also serves as social language. Culture, education, and identity shape what we value and what we signal through our preferences.

In this framework, lower levels (biology, neural processing…) provide the foundation, while higher levels (cognition, emotion, social context…) can override or amplify basic responses. Let’s look at each of them more closely.

The biological foundations of taste

Sensory gatekeepers

You walk into a gallery and pause before a painting of a landscape. It is quite small, so you need to get close to see it clearly.

Any aesthetic experience begins with biology: our sensory apparatus. Quite literally, we cannot enjoy a painting if we are blind, or music if deaf.

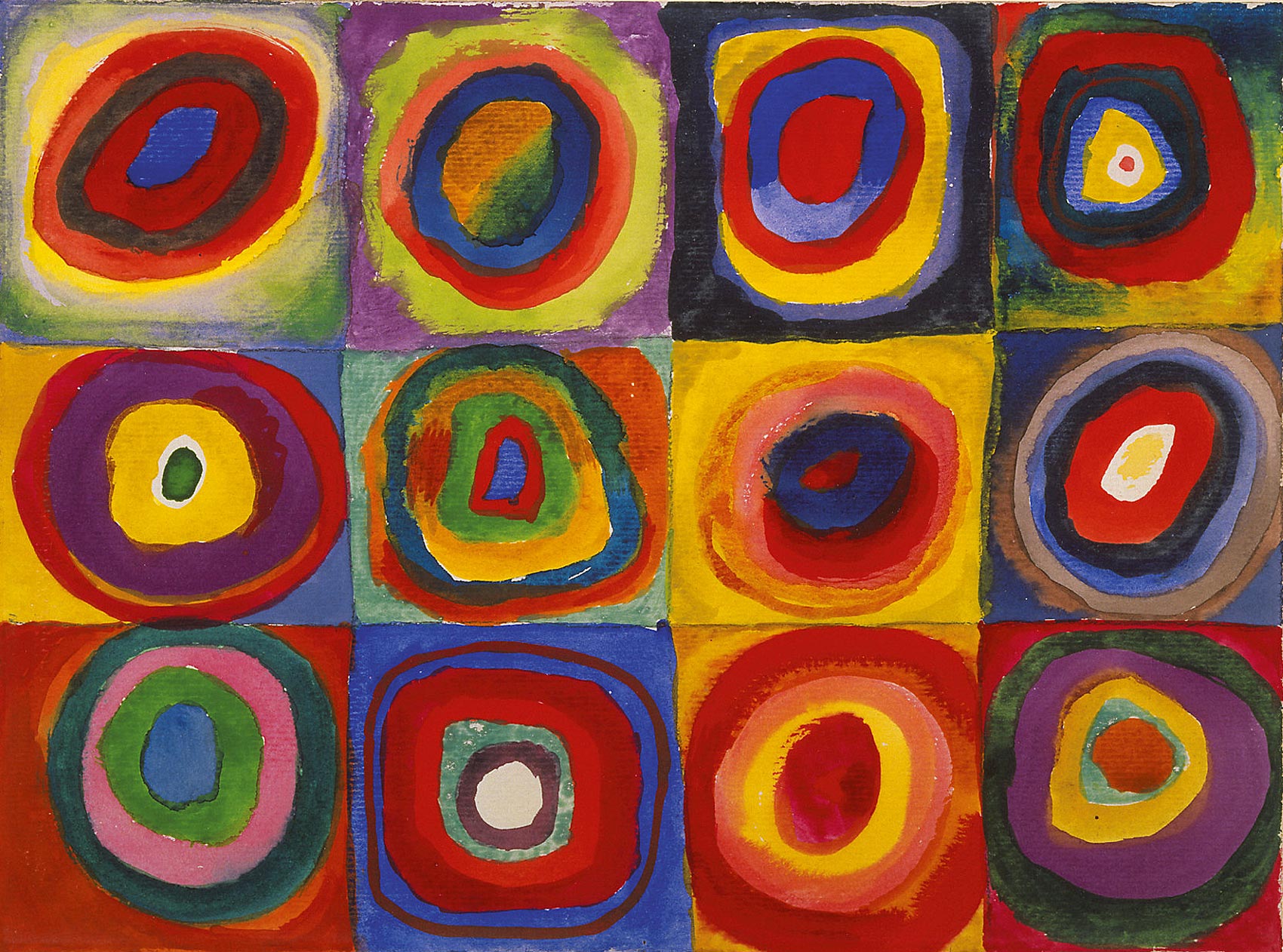

But this gets a little more nuanced: sensory clarity can increase or decrease appreciation. Being colorblind may be frustrating if one cannot distinguish all the colors in Kandinsky’s Colour Study, yet this limitation can also give rise to a new perception of the painting, one that may be more or less pleasant than what the artist intended.

Similarly, not being able to hear frequencies above 15,000 hertz might exclude part of a song from the listener’s awareness, but this could actually improve the experience if the song includes a piercing high tone!

In general, we assume that perceiving more detail enhances aesthetic appreciation, since it offers greater fidelity to the artist’s “original vision”. Most people prefer watching a film on a wide IMAX screen rather than on an old TV. Yet there are exceptions: vinyl records, for instance, introduce a warm, low-pass filter that many find pleasing.

Everyone’s sensory equipment is slightly different, so no two people encounter an artwork in exactly the same way. There isn’t a single “true” perception, but senses become the first modulator of taste.

Evolutionary preferences

In the painting, the depiction of a lush valley and lake immediately evokes a sense of peace and safety. You feel like you could “live” there.

Evolution has tuned our brains to prefer some stimuli over others because they were historically advantageous or safe.

For instance, humans generally enjoy harmonious sounds and are distressed by discordant noise or screams, likely because in nature a scream signals danger (or a hungry child). We tend to find landscapes with blue skies and greenery beautiful, perhaps because they subconsciously promise water and shelter (see Zhang et al. 2018, for example).

These biases hint at an objective core to taste rooted in survival: nobody’s favorite sound is a baby’s wail or nails on a chalkboard, and no culture glorifies the smell of rot. Such universal repulsions/affinities suggest that aesthetic preferences are initially constrained by our shared neurobiology. They form a baseline “bio-esthetic” layer of taste.

The role of symmetry

Somehow, the contrast of colors, the soft play of light and shadow, the even brush strokes and the symmetrical composition produce a sense of harmony within you.

One clear example of an innate bias is symmetry. Symmetrical patterns in art, design, or faces are widely considered attractive.

Neuroscience shows that symmetry is processed efficiently by the visual system. Even young children gaze longer at symmetrical images (indicating interest), though they don’t explicitly prefer them until older, implying that exposure later converts that attention into actually liking (Huang et al. 2018).

The fact that symmetry is immediately parsed by our low-level perception suggests it provides a kind of neural fluency or ease that is experienced as pleasing. Brain imaging (Sasaki et al. 2005) confirms that viewing symmetrical visuals leads to more robust activation in the lateral occipital cortex and other visual areas associated with shape processing. In other words, symmetry makes the visual cortex’s job easier, and this processing fluency may translate into a “positive” aesthetic response. But symmetry’s role in taste might go even deeper than perceptual ease.

Principia Qualia (2016) is a groundbreaking work by researcher and philosopher Mike Johnson. In it, Johnson argues that every moment of experience (qualia) can be represented as a mathematical object (a view known as qualia structuralism).

A central concept in the book is valence, the felt quality of how good or bad an experience is. According to Johnson’s Symmetry Theory of Valence (sometimes mentioned as STV here), the more symmetrical the mathematical structure of a given experience, the more pleasant it feels. Symmetry not just in the world or in perception, but in the shape of consciousness itself.

While we don’t know yet the exact mapping between brain activity and qualia, STV offers a compelling hypothesis: pleasant or “beautiful” experiences come from more ordered brain activity, and unpleasant ones from disorder. In other words, there may be a direct link between how organized our neural patterns are and how good a moment feels. When the brain is in a smooth, coherent rhythm, the experience feels harmonious; when its activity turns chaotic, it feels tense or unpleasant.

This idea is supported by music perception research. Bidelman and Krishnan (2009), for instance, showed that consonant musical intervals (those with simple frequency ratios) produce stronger and more phase-locked responses in the auditory nerve than dissonant ones. In other words, consonance literally triggers a more “orderly” neural signal.

Pleasant music also activates the brain’s reward centers. For example, dopamine is released in the striatum when a musical piece “peaks” into a satisfying harmony or melodic resolution (Salimpoor et al, 2011; Zatorre and Salimpoor, 2013). As Ball (2012) notes in Why Dissonant Music Strikes the Wrong Chord in the Brain, our aversion to dissonance likely stems from the way overlapping overtones confuse the auditory system. When tones fail to form a neat harmonic series, the brain struggles to easily interpret them, and the experience feels less rewarding.

Taken together, these findings align with the idea that neural consonance = pleasure. Our biology favors stimuli that the brain can encode in an orderly way. It’s as if the brain rewards stimuli that make “sense” to it at a fundamental level. We experience the alignment of neurons in coordinated patterns as aesthetically satisfying.

This gives another “objective” dimension to taste: certain structural qualities (symmetry, balance, proportionality) reliably engage human brains and give pleasure. Of course, this does not mean that only simple patterns are enjoyed (almost no one drools over a simple black circle on a white sheet). As we’ll see later, the brain also craves challenge and complexity, but it does mean that at a given level of complexity, the more internally coherent and symmetrical the experience, the more it tends toward beauty (in the sense of positive emotional valence).

Symmetry across brains

Interestingly, when art is especially well-crafted, it tends to synchronise not only neurons within one brain, but also across different brains!

In cinema, Hasson et al (2008) have shown that when multiple people watch the same (engaging) film, their brain activity patterns become highly correlated, especially in higher-order regions like the prefrontal cortex and limbic areas. The phenomenon is called inter-subject correlation or “neural synchrony.”

This is based on an earlier experiment (Hasson et al, 2004) where viewers’ brains “ticked collectively” while watching The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, not just in basic visual areas but also in emotional and narrative-processing regions.

Later studies confirmed that this synchrony is strongest when the story is coherent or engaging, and decreases when clips are scrambled or meaningless (Jääskeläinen, 2008). This suggests a kind of interpersonal symmetry: structured works could bring different minds into the same dynamic pattern.

That alignment is likely part of why the structured film is more enjoyable and engaging. It literally puts different viewers on the same wavelength. From the perspective of our theory, this is another compelling biological basis for what we perceive as agreed-upon ‘good’ design, or hinting at an underlying, shared neural susceptibility to certain artistic structures. This means that certain configurations of stimuli can drive a human brain (or almost any human brain) into a particular pleasurable state.

There’s no guarantee that an alien brain would respond the same way to the same stimuli, but translated into a way it could parse, there is also no reason why it wouldn’t.

In summary, the biological layer of taste gives us a foundation: we enjoy what our brains are easily able to process, especially if it hints at things that are evolutionarily beneficial for us (like safe environments or social cohesion). Symmetry, harmonious patterns, and familiar forms tickle our neural circuits in satisfying ways. But if this were the whole story, all art would be simple and universally liked, which it obviously isn’t. Humans also seek complexity, surprises, and personal meaning in art. To understand that, we need to turn to the cognitive layer of taste.

The cognitive layers of taste

The brain as a prediction machine

You expect a straightforward landscape, but then you notice a tiny, almost hidden figure of a lone shepherdess in the foreground, easily missed at first glance. This unexpected detail is a pleasing dose of surprise. She adds a human element without disrupting the overall serenity, offering a fresh point of focus, subtly deepening your interest.

Modern theories of perception, like the predictive coding model, suggest that the brain is constantly making predictions about incoming sensory data and then updating itself based on the errors (mismatches) between expectation and reality. (Rao & Ballard, 1999, Friston, 2005).

For example, before reading this sentence, you probably weren’t aware of the feeling of your clothes against your skin. Constantly sending that information to consciousness would be costly and unnecessary, so the the brain filters it out (unless something truly unexpected happens, like a sudden itch or change in pressure). You also probably didn’t notice the double “the” in the previous sentence. Your brain predicted that two “the"s shouldn’t occur in a row, so it simply skipped over it.

This filtering mechanism lets us move through daily life efficiently. In aesthetic contexts, it provides the pleasure of surprise: we enjoy works that play with our predictions, neither totally predictable nor totally random, but a clever mix of both.

Think of a melody in a song: if the next note were completely obvious, the tune would be boring; if notes were thrown together with no structure, it would sound like noise (although noise can sometimes be enjoyable, but we’ll get to that). The best melodies set up patterns and then introduce a slight deviation or a delayed resolution, gratifying us when the pattern completes.

Neuroscientist Wolfram Schultz demonstrated this principle through studies of dopamine neurons (Schultz et al. 1993): dopamine spikes when an outcome is better than expected, a “positive reward” prediction error. Applied to aesthetics, this means that artworks are enjoyable when they manage our prediction errors artfully, giving us enough clarity to form expectations, then violating them in interesting ways.

Supporting this, Salimpoor et al. (2013) found through fMRI that moments of musical “chills” coincide with strong communication between the auditory cortex (which anticipates patterns) and the nucleus accumbens (a dopamine reward center). Pleasure arises not from recognition or surprise alone, but from their dialogue: the brain predicting, being surprised, and then rewarding itself for understanding.

Culture sets these priors (another term for “predictions”) very early. Studies on infants (Soley & Hannon, 2010) show that by 6 months old, babies already prefer the musical intervals that’s common in their culture’s music! This isn’t because biology differs, but because the brain has been trained on different patterns.

This same mechanism explains why we crave novelty. Our brains are attracted to the new and unexpected, up to a point. A completely novel stimulus (with no recognizable patterns) might just confuse us, but a slightly novel twist on an existing pattern is exciting.

Novelty triggers the release of dopamine (Costa et al., 2018). Psychologically, this makes sense: exploring new stimuli can lead to discovering valuable things (new foods, new environments), so evolution wired us to feel good about novelty (or at least to dislike boredom). In art, novelty refreshes our attention and can elevate pleasure by violating expectations in a safe context.

Another 2019 fMRI study, by Cheung et al. showed that musical pleasure peaks when predictability and surprise are balanced. They analyzed over 80,000 chords in popular songs and found that people rate songs higher when they hit one of two sweet spots, either:

- Low uncertainty + high surprise (you expect something, and it surprises you pleasantly)

- High uncertainty + low surprise (you’re not sure what to expect, but the piece stays relatively within an acceptable range).

So, the sweet spot is “bounded novelty”: enough familiarity to latch onto, enough surprise to be intriguing. This is why many pop songs follow a standard structure (verses and chorus) but add a bridge or a key change; why a thriller movie adheres to genre conventions but includes plot twists; or why a painting might respect form but use novel color combinations.

Even experimental art obeys the same logic. Let’s take the works of Merzbow, for example, which often consist of layers of very harsh static and feedback: can there be structure in pure noise? Fans claim there is. It might not be melodic structure, but there are textures, dynamics (changes in loudness/timbre over time), and an emotional arc to the noise.

Our theory would suggest that even in noise, the brain latches onto any motifs or patterns. If literally none existed, “true” white noise would result, and indeed, virtually no one would enjoy listening to random white noise for long. But noise and drone music usually isn’t truly random: artists manipulate it to create tension and release. Listeners with practice start anticipating these shifts, creating a form of predictive engagement. Where there is any discoverable pattern, there can be aesthetic pleasure.

To summarize, effective art creates an optimal level of prediction error. We literally get chemical rewards for learning and pattern-matching when the puzzle is solvable.

This mechanism can also be used to argue for some human-level objectivity (intersubjectivity?) in taste: as a species, civilization, or culture, we share a lot of the same “predictions.” Our brains are tuned by the same biology and trained by overlapping patterns. These priors form a common basis for our aesthetic taste.

The familiarity principle

One well documented finding in psychology is the mere exposure effect. People tend to rate things more favorably if they’ve been exposed to them before (even without conscious memory of it). In aesthetics, familiarity often leads to liking (up to a point). You have probably experienced it when hearing a song on the radio. The first time, it felt weird and uninspired. Ten times later, you were singing along with it.

Familiarity serves as a way to train the brain to find the pattern: what was initially just noise becomes music once you learn its structure. This is why exposure can smooth out “dissonance” into “consonance”. With familiarity, you start to perceive order in it and it bothers you less.

On the flip side, over-exposure can cause liking to reverse due to boredom (it becomes too predictable now). A novice ear might only catch simple patterns and thus prefer simple music; while a trained ear, having access to and integrating more patterns, can appreciate complexity and might find simple music uninteresting.

Relatedly, the “value” of an artwork is usually revealed through exposure and familiarity. You may enjoy watching Transformers the first time, but resistance to watching it again could be a sign that its appeal is… limited? By contrast, your first viewing of 2001: A Space Odyssey might leave you very confused, but curious. Each rewatch reveals new layers, and your appreciation of it increases because your mind keeps discovering patterns to enjoy.

To sum up here: every time we encounter new art, we are updating our predictive model of the world. The broader and richer that model, the more sophisticated patterns we can enjoy. This is an encouraging aspect of taste, because this means it can grow with us.

Meaning and conceptual symmetry

You connect the shepherdess with the vast landscape, and a deeper meaning shows up: perhaps it’s about humanity’s small place in nature, or the silent dignity of labor. This conceptual understanding brings a sense of intellectual satisfaction, elevating the painting from merely pretty to meaningful.

Beyond just raw sensory patterns, humans are driven to find meaning in what they perceive. We are storytelling creatures who seek coherence not only in sounds and shapes, but in ideas and emotions. Thus, a huge part of taste (especially for complex or abstract art) involves cognitive interpretation.

An abstract painting or a seemingly nonsensical film might not have obvious symmetry or pattern on the surface, but as viewers, we try to impose or discover pattern at a higher level: “What could this represent? What feeling or concept emerges?”

The process of sense-making itself can be pleasurable when it clicks. Psychological studies like Muth & Carbon, 2023 have suggested that people often derive enjoyment from interpreting artworks, as the moment of “Aha, I see what this might mean” is rewarding.

In terms of our theory, we could say the mind achieves a kind of cognitive symmetry in that moment: separate elements of the work suddenly form a unified picture or concept in the mind, which is experienced as satisfying. For example, take a complex film like David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. On first viewing, you might be like: “???”

But with effort and probably multiple viewings (like we mentioned for the familiarity principle), you can piece together a plausible narrative or thematic interpretation that makes the strange scenes fit into a coherent whole. When that understanding crystallizes, the previously bizarre elements now seem cleverly interconnected. You have transformed mental chaos into order.

An interesting paper on the topic is Aviv’s 2014 “What does the brain tell us about abstract art?”. From the abstract:

[…] Abstract art frees our brain from the dominance of reality, enabling it to flow within its inner states, create new emotional and cognitive associations, and activate brain-states that are otherwise harder to access. This process is apparently rewarding as it enables the exploration of yet undiscovered inner territories of the viewer’s brain.

Because abstract art doesn’t depict a clear object or scene, it invites viewers to project their own imagination and feelings onto it. This process can lead to novel insights or resonances unique to each viewer, making the experience of the art a creative act itself.

In other terms, the reward (dopamine, satisfaction…) comes from the viewer actively finding some interpretation or personal meaning, a symmetry between the art and one’s internal thoughts. This could explain why some people love abstract or surreal art: it engages their cognitive-emotional machinery deeply, even if on the surface it might lack the easy appeal of a pretty landscape.

The Symmetry Theory of Valence is thus extended here: again, it’s not the symmetry of the physical stimulus that matters, but the symmetry (integration, harmony) of the mental state it induces. If a piece of art initially creates mental “dissonance” but eventually the viewer reorganizes their understanding into a coherent pattern, the resulting mental state might be even more satisfying (a higher peak of valence) than a simple, easy artwork.

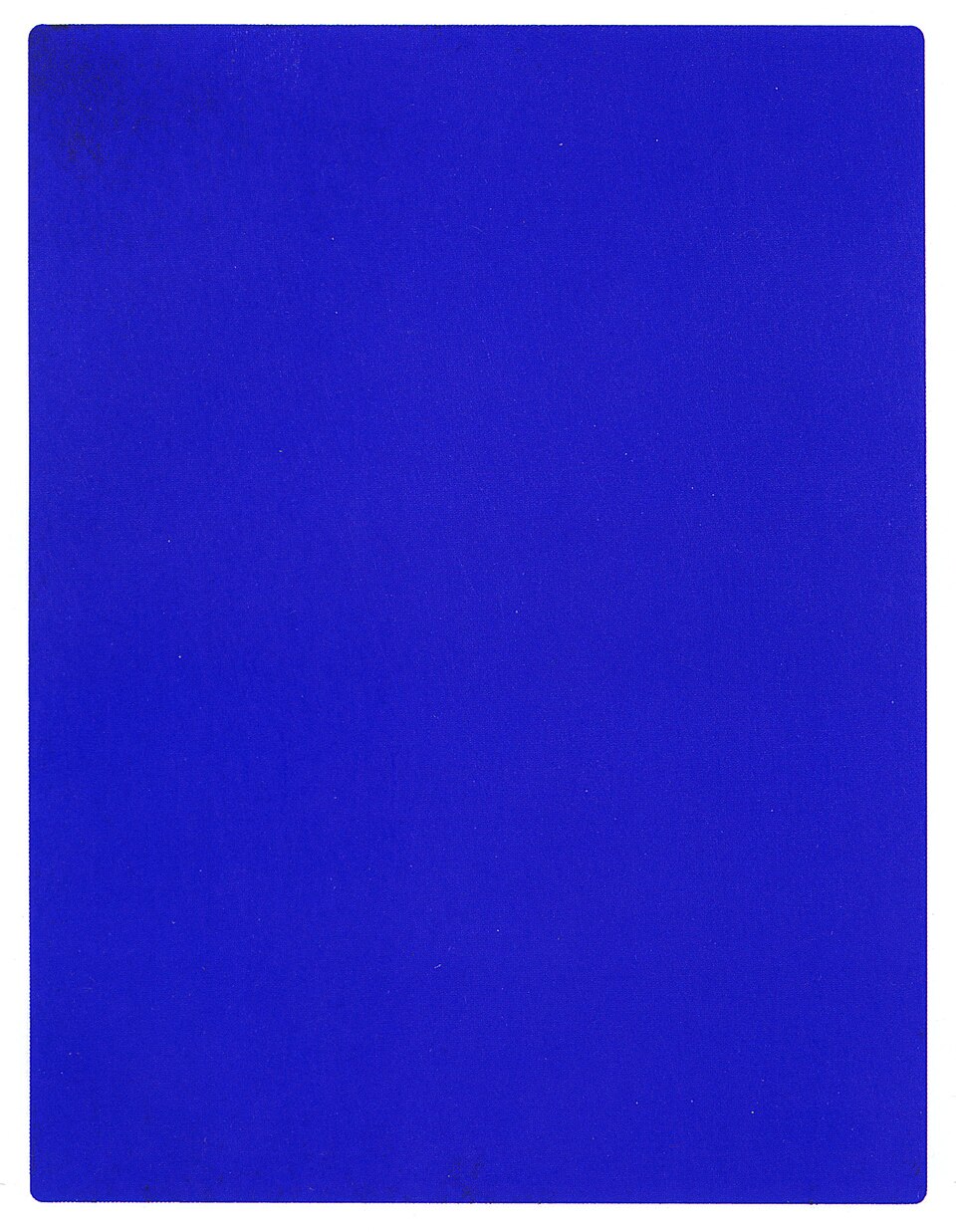

Minimalism takes a reverse approach. A single-color canvas, like paintings by Yves Klein, challenges us not with complexity but with another type of abstraction. Some may start by thinking “it’s just blue,” but then, in the gallery context, with the intensity of the color, the textures of the surface, and the meditative feeling of focusing on “nothing”, interesting things may happen.

The symmetry or pattern here is almost entirely in the conceptual realm. The canvas is a prompt for a certain mental state (calm, infinite, void…). The absence of complexity in this art forces the pattern-seeking activity to go inward (to the viewer’s own mind or to philosophical ideas, for example). This is why many minimalist works are explicitly about invoking contemplation. In a way, they reduce external stimulus so that our internal cognition can take over in creating order.

We can only ever judge our total experience of an artwork. If an extremely simple painting can elicit intense (positive) emotions, its simplicity is not a disadvantage, but a feature.

Emotional coherence and catharsis

As you stand there, the soft light of the valley, combined with the solitary figure, evoke a powerful sense of nostalgia, maybe bringing up a childhood memory. You feel a sense of longing, making the painting resonate profoundly on an emotional level.

It feels obvious to state, but emotions are integral to taste. Often, what we describe as a matter of taste (e.g., a love for tragic dramas, or a distaste for horror movies) boils down to what emotions we are comfortable experiencing in an artistic context.

One puzzling question is: Why do people enjoy “sad” art or “scary” art, when sadness and fear in real life are unpleasant? Our framework suggests a resolution: art provides a safe frame for experiencing negative emotions. Fiction lowers the real-world cost of engaging with fear or sadness while providing structure through narrative, motifs, or pacing.

This is the classic idea of catharsis: purging or transforming emotion through art. When a movie makes us cry but in the end we feel uplifted or reflective, it has taken a raw feeling (like grief) and given it shape, purpose, creating emotional coherence.

For example, you probably don’t enjoy being sad in life, but you might deeply appreciate a sad song that resonates with your own loss and then resolves in a beautiful harmony, because it makes your inner state feel seen and organized.

There’s some evidence for this in studies on narrative and empathy. For instance, Hsu et al. (2014) found that reading emotional fiction activates the brain’s pain and empathy networks.

We presented participants with text passages from the Harry Potter series in a functional MRI experiment and collected post-hoc immersion ratings, comparing the neural correlates of passage mean immersion ratings when reading fear-inducing versus neutral contents.

Results for the conjunction contrast of baseline brain activity of reading irrespective of emotional content against baseline were in line with previous studies on text comprehension. In line with the fiction feeling hypothesis, immersion ratings were significantly higher for fear-inducing than for neutral passages, and activity in the mid-cingulate cortex correlated more strongly with immersion ratings of fear-inducing than of neutral passages.

Descriptions of protagonists’ pain or personal distress featured in the fear-inducing passages apparently caused increasing involvement of the core structure of pain and affective empathy the more readers immersed in the text.

Art can make even pain pleasing by giving it form and connection, creating a kind of emotional symmetry.

But not all pleasure comes from resolution. Some works sustain ambiguity and discomfort while remaining compelling because the unease itself is structured and intentional. Michael Haneke’s films are good examples here. Funny Games or Caché are relentlessly tense and never reward us with a happy resolution. Yet, because the discomfort is carefully shaped through deliberate choices, it becomes engaging rather than unbearable (“It hurts so good”).

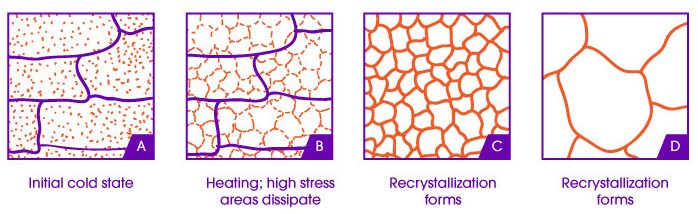

Neural annealing

This brings us to another powerful (but still speculative) model from Michael Johnson and the Qualia Research Institute for why resolving such intense complexity can be so rewarding: neural annealing.

Drawing from theories on consciousness and thermodynamics, this idea suggests that our neural pathways have properties similar to metal, which can be heated up and given a new, more robust shape when it gets too brittle.

Here, engaging with complex, ambiguous, or dissonant art could act like “heat” on the brain’s dynamics. The cognitive effort of trying to find patterns where none are obvious throws the system into a higher-entropy, more plastic state (because of the energy spent on processing these patterns). If the artwork contains symmetries (whether structural, thematic, or emotional), the brain can then “cool” or “anneal” into a new, more stable, and highly coherent configuration. The more “heat” (i.e., the more profound the initial challenge), the deeper and more satisfying the resulting state of order can be. Complex art, therefore, offers a greater opportunity for this transformative reorganization, explaining why the pleasure derived from it can feel more profound than that from simpler, more predictable stimuli.

These processes, through neuroplasticity, could sculpt our long-term consciousness. Remember: our brains, as seen before, are prediction machines optimized to anticipate and generate patterns they encounter frequently. So, someone who has been engaging with art characterized by anxiety or anger may be strengthening neural networks that default to these states. The other way around, consistent exposure to art with harmonious structures and positive resolution may build robust and positive “attractor states”.

This shaping happens both over time and in the moment. While consistent exposure shapes our “mental landscape”, a single piece of art can instantly alter our mood and physical state. I remember leaving the theatre after watching The Substance. While enjoyable in the moment, the movie left me in a state of unease for hours afterwards, negatively coloring my perception of the world.

Psychedelics also reveal this clearly: when tripping, “bad-vibe” art (the definition of which seems very clear in such states) can feel deeply jarring, while “good-vibe” art is extremely appealing.

Scott Alexander in Singing The Blues:

Millgram et al (2015) find that depressed people prefer to listen to sad rather than happy music. This matches personal experience; when I’m feeling down, I also prefer sad music. But why? Try setting aside all your internal human knowledge: wouldn’t it make more sense for sad people to listen to happy music, to cheer themselves up?

A later study asks depressed people why they do this. They say that sad music makes them feel better, because it’s more “relaxing” than happy music. They’re wrong. Other studies have shown that listening to sad music makes depressed people feel worse, just like you’d expect. And listening to happy music makes them feel better; they just won’t do it.

I prefer Millgram’s explanation: there’s something strange about depressed people’s mood regulation. They deliberately choose activities that push them into sadder rather than happier moods. This explains not just why they prefer sad music, but sad environments (eg staying in a dark room), sad activities (avoiding their friends and hobbies), and sad trains of thought (ruminating on their worst features and on everything wrong with their lives).

This has significant implications beyond personal preference. Our aesthetic consumption acts like slow-motion cognitive behavioral therapy. Every piece of art we engage with helps to sculpt the “attractor landscape” of our minds, the states our minds default to.

If true, this elevates taste cultivation to a sort of mental health practice: each aesthetic choice becomes a small “push” towards the neural landscape we want to inhabit. Going further, this highlights an ethical dimension of taste: beyond catharsis or critique, societies need a steady supply of art that fosters coherence, joy, and compassion.

So, to summarize the cognitive layer: our tastes evolve and sharpen as we learn to discern patterns at higher levels (structural, conceptual, emotional) and as our predictive brains seek an optimal balance of familiarity and novelty. Every encounter with art refines our internal model of the world, expanding what we can recognize and enjoy.

But, beyond these momentary highs, repeated engagement also sculpts the brain’s attractor landscape through neuroplasticity. Exposure to certain artistic structures can deepen the grooves of coherence or of fragmentation.

The “objective” component here is the underlying cognitive mechanism which operates similarly in all brains, and the subjective part is how much pattern one has learned to detect. This should lead to the idea that taste can be improved or refined by experience. Before addressing that, let’s add in the final piece of the puzzle: the social dimension of taste.

The social layers

No one’s taste develops in a vacuum. We are social creatures, and our aesthetic preferences are profoundly shaped by cultural context, peers, education, and considerations of status and identity. This social layer doesn’t override the biological or cognitive ones, but it constantly interacts with them, amplifying or muting them, and sometimes introducing new motives, like the desire to belong. In this framework, two dynamics stand out: knowledge and framing, and status and identity.

Informational context and knowledge

You move next to the painting to read the plaque, hoping to learn about the artist’s inspiration. Instead you read: ‘Morning Light on the Valley by Sarah Williams (c. 1885). Scholars now believe many elements were lifted directly from an earlier painting by Agnes Dubois.’ The serene valley you admired a moment ago now feels… compromised? It’s still pretty, but knowing it’s largely borrowed deflates the sense of originality and genius.

Apart from the direct sensory experience, what you know about an artwork or art form dramatically colors your taste.

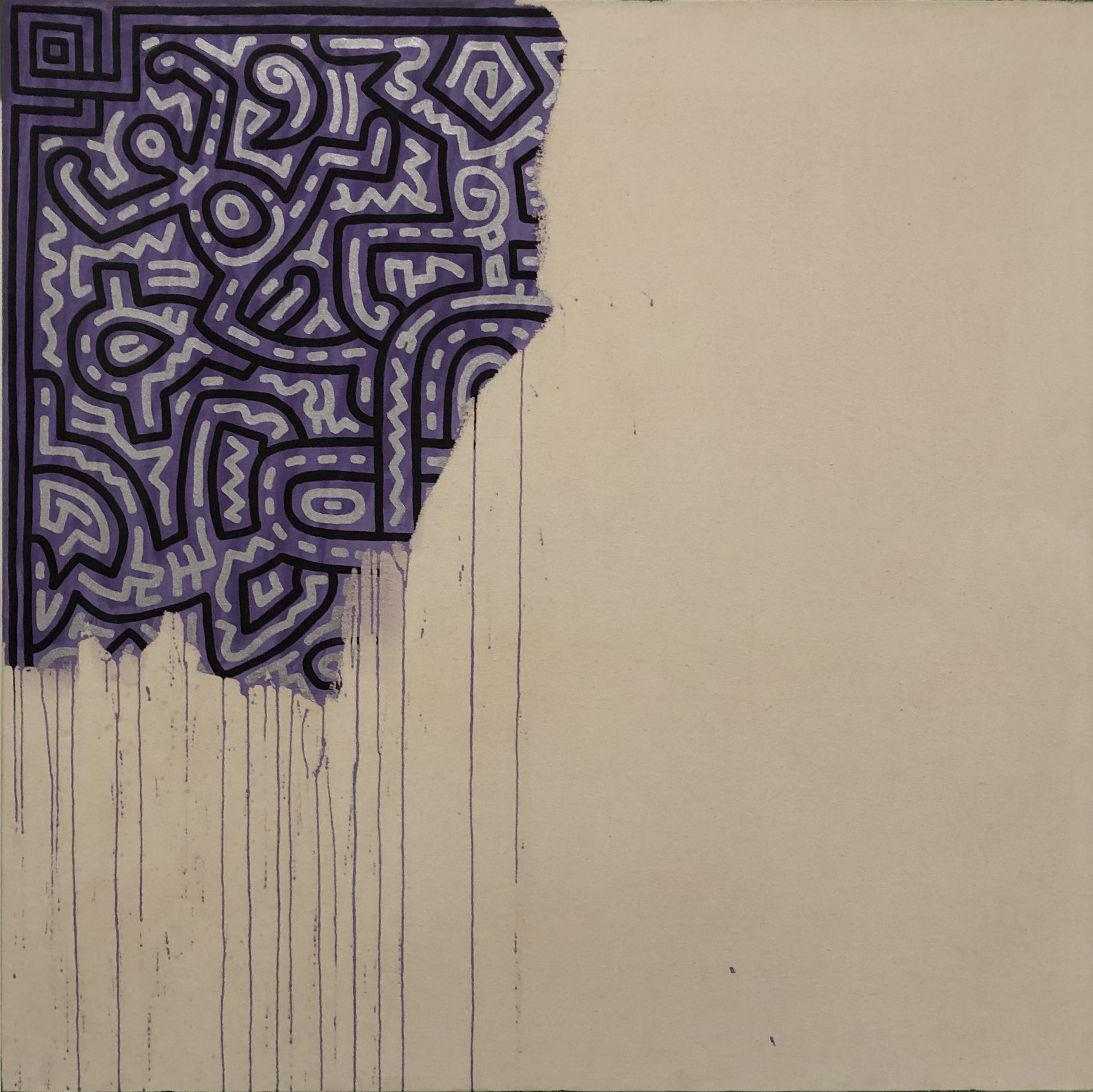

Context can transform an experience. For example, imagine viewing a painting only a quarter finished, with a few blue lines dripping on the rest of the canvas. Without context, you might dismiss it as childlike doodling. But if you learn that it was purposely left unfinished by an artist who knew he was going to die tragically, suddenly those lines carry emotional weight. You suddenly see the intent, the narrative behind the piece.

This painting might move you to tears knowing its context, whereas it did nothing for you before. The information created a higher-order pattern, connecting the art to a story, which produces meaning and, through meaning, aesthetic impact.

Many artworks (and certainly most conceptual art) rely on context to be appreciated. When Marcel Duchamp displayed a urinal as Fountain in 1917, the object itself wasn’t aesthetically pleasing, but understanding the context , a statement about what counts as art (classic Dadaist provocation) - could allow one to appreciate its wit and boldness.

Knowledge can thus resolve initial aesthetic dissonance. It’s like giving the brain a key to decode an encrypted message. Before, the brain found no pattern (and thus no pleasure); after, it sees the pattern or purpose and aligns with it. It’s a subtle nudge to help your brain know how to reorganize itself in order to experience and appreciate the artwork.

A Model of Aesthetic Appreciation and Aesthetic Judgments by Leder et al. (2004) is very informative here. While the paper states that information doesn’t always improve preference, it points to studies where participants appreciated abstract art more once they were given background information or interpretive cues, showing that knowledge can increase processing fluency and unlock meaning.

But there’s more. In an experiment by Huang et al. (2011), participants viewed Rembrandt paintings and copies while being told each was either ‘authentic’ or not. Interestingly, their brain activity changed with the label, not with the image. When a painting was believed authentic, areas involved in attention and valuation lit up more strongly, even if the picture was actually the copy.

The same thing was found by Kirk et al. (2009): artworks randomly tagged as “from a gallery” were rated more highly than the ones tagged as “computer-generated”. In both cases, the art is the same, but its context, the narrative surrounding it, directly alters how our brains light up and process the experience.

The social-informational layer of taste is powerful. It’s the reason art historians, music critics, and educators exist: to enrich our experience by adding context. You can try it for yourself. The Youtube channel Great Art Explained is wonderful at dissecting famous artworks and placing them in a historical and artistic context. I personally find that after watching one of these videos, my appreciation for the piece has increased significantly.

Another example I like here is Adaptation, written by Charlie Kaufman. This movie tells the story of a screenwriter named Charlie who’s hired to adapt a nonfiction book about orchids, but instead spirals into writer’s block. What makes it extraordinary is that this is the actual film Charlie Kaufman delivered: in real life, he was hired to adapt The Orchid Thief, couldn’t figure out how, and instead wrote a movie about himself and his inability to write the movie. Knowing that this is all real makes the experience more delightful. The perceived added value is not in the art “itself”, but rather in the context surrounding it.

To emphasize the point: you might assume that a painting is judged purely by its colors and textures, confined to what’s visible on the canvas. But in reality, what you evaluate is the total experience, including what you know, remember, and feel. You can’t simply switch off the part of your brain that processes meaning, memory, and associations. Neurons that fire together influence perception and they tend to avoid cognitive dissonance. That’s why, no matter how pleasing the raw sensory data might be, your favorite painting is unlikely to have been painted by Adolf Hitler.

AI art

At the time of writing, there is a lot of societal confusion about AI art. Can it be better than human art? Will all media we consume in the future be generated by algorithms? So, I figured it would be useful to add a little aparté here to apply our theory to AI art.

Art generated by prompted-programs highlights the importance of context more clearly than almost anything else. On the surface, machine-made works can look great! They can excel in the lower layers such as symmetry, color balance, melodic consonance, generating emotion, or simply recreating styles we are all familiar with. These biological and instinctive cues are easy to generate with enough training data, which explains the instant appeal of many AI images or songs.

But informational and social context is where AI falls short. Again, without conscious experience, AI can only synthesize and react to prompts, but can’t come up with something infused with personal meaning or backstory. Once you learn that a work was machine-made, your judgment of it often deflates. It’s not profound anymore, it becomes “soulless.”

I think this explains the paradox: AI art can be pleasing at first sight, but it rarely generates depth because the higher layers (cognitive innovation, emotional resonance grounded in experience, informational and social meaning…) are missing or borrowed. Human art often grows in richness the more you know about it, the opposite could be said for AI art.

Still, intent can change everything. Suppose an artist whose style had been somehow copied or stolen reemerges after a decade with a new work made entirely with DALL-E. In that case, the piece would resonate not just as an image but as a statement (or a self-deprecating joke). The context reintroduces higher-layer symmetry, making the work meaningful in ways the machine alone could not achieve.

With this out of the way, let’s go back to our last layer.

Status games

Whether you like it or not, taste is also a social currency. What you claim to like (or dislike) can be a signal to others about your identity, education, or status.

“Cultural capital” was a concept very dear to sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Members of a higher socio-economic class often cultivate tastes in more obscure or historically esteemed art forms (opera, avant-garde art, fine wine…) as a way to distinguish themselves from others. This means that sometimes people pretend to like things less for the sensory pleasure and more for the social reward.

Our theory recognizes this and fully accounts for it. In the “status layer” of taste, a person might derive enjoyment not from the art itself but from being seen as someone who has that taste. For instance, an individual might not truly enjoy atonal free jazz, but they might say they do (and even force themselves to try to enjoy it) because it confers an image of sophistication.

And taste doesn’t only signal sophistication, it can also signal morality. In many cases, we don’t just like art because it resonates aesthetically, we like it because it aligns with our political or ethical identity. Liking a protest song or a socially conscious film can function as a badge of belonging: “I am a good person.”

Thus, we can view status-driven taste as a kind of secondary conditioning: the brain’s reward system can attach positive value to an artwork if appreciating it results in social praise or a sense of belonging to a group. Social approval releases dopamine too! In such cases, the symmetry or pleasure isn’t coming from the artwork’s intrinsic properties or one’s own pattern recognition, but from an external feedback loop of human prestige. Again, we can only ever rate our experience of an artwork.

All this can complicate measuring genuine aesthetic value, but importantly, it doesn’t mean taste is entirely snobbery or social construction. Even the snob who pretends to like experimental art likely had to engage with it enough that some authentic appreciation developed (or else they’d be immediately outed as a poser).

Moreover, not all refined taste is status-driven. As we’ve seen, being able to enjoy complexity comes from exposure and increased perceptual capabilities. Still, the social layer reminds us that taste has a performative aspect in human society. Ideally, we should strive to disentangle whether we like something because of how it makes us feel versus how it makes us look to others. In many cases though, both factors mix together.

In our unified theory, the social layer shows how taste is not just private judgment but also socially constructed. Information reframes perception: context, authorship, or history can modulate our evaluation of the very same work. Status further complicates things, as what we claim to like can also act as a signal of sophistication or moral identity. And because approval itself is rewarding, the brain can learn to associate art with belonging as much as with beauty.

These mechanisms mean that social context can both expand and distort taste: it can cultivate a richer appreciation through education and shared meaning, or it can narrow our horizons by rewarding conformity and signaling over genuine resonance.

Having examined the biological, cognitive, and social dimensions that shape taste, we can now address why improving one’s taste is a worthwhile endeavor.

A tasteful new world

One major claim of our theory is that refining taste enables the creation and appreciation of more complex, vibrant art, and that this advancement is beneficial for culture and society. But why exactly?

The richness of complex art

By “complex art,” we can mean works that have multiple layers of structure or meaning. Examples might range from a symphony that weaves multiple themes over an hour, to a play that breaks the fourth wall deliberately, to a gothic cathedral filled with symbolic detail, etc.

Works like these often provide a richer experience than simpler ones because they can evoke a broader range of responses. As noted earlier, simple art can give direct pleasure quickly, but it often maxes out at a certain point, whereas complex art can yield new insights and feelings upon each encounter.

Complex art can layer joy and melancholy, awe and introspection, producing “depth of resonance.” Again, going back to the symmetry theory of valence and our layer models of taste, we can say that complex art has more opportunity for symmetry, as it can happen across more layers.

But complexity doesn’t always have to arise only from meaning or symbolism. It can also come from the structure or the scope of the piece of art. Why do we tend to prefer a whole song to a single verse, or an album to an isolated track? Often, the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts.

For example:

- A simple melody offers a basic “symmetry”. It has its own inherent order and pleasing patterns.

- A song, however, introduces more intricate symmetries. It meshes together multiple melodies, rhythms, harmonies, and lyrical themes, creating a richer, more complex, yet still resolvable, structure. This stacking of “more symmetrical layers” across sensory and emotional dimensions leads to a more profound and lasting positive experience.

- An album takes this a step further by weaving “motifs across tracks”. It can develop themes, sonic palettes, and emotional arcs over a longer duration, creating an even more elaborate and interconnected symmetrical structure. This increased complexity, when successfully resolved and integrated by the listener’s mind, yields an even deeper and more multifaceted aesthetic pleasure.

Quick aside: not all great art is multi‑layered, though. Some works achieve greatness by driving just a few layers to saturation. A perfect pop song can be unforgettable without much interpretive scaffolding if it just “saturates” the lower layers (groove, melody, timbre…).

And finally, complexity on its own isn’t enough. A drummer playing at lightspeed level is impressive, but without rhythm or structure it just sounds like incoherent noise. What makes complex art rewarding is when all the extra parts fit together into something coherent.

In other words, it’s not about how much is going on, but whether it clicks into a pattern that “feels” right.

Refined taste as enabler

Without a sufficiently refined taste, we might miss the rewards of complex art. To an untrained palate, a gourmet dish might just taste “weird,” but to a trained palate, it’s an explosion of nuanced flavors.

Likewise, refined listeners or viewers can detect and appreciate the layers in complex art. And this is a virtuous cycle: as we refine our taste and hunger for more complexity or novelty, artists are pushed to create innovative works to satisfy their audience. If no audience member could tell the difference, why would Bach bother writing an intricate fugue when a simple jingle (or whatever the musical equivalent of that time was) would do?

But when a refined taste audience exists, it pulls art upward. Many of history’s greatest artworks were not mass-appeal works in their time (The Rite of Spring caused a riot during its premiere because of its dissonance and complexity…); they were created for a discerning audience or for the artist’s own high standards, and only later did philistines catch up. When those works eventually reach a broader public (as taste collectively improves or at least the works become more familiar), they often raise the bar for what is considered possible in art.

Cultural evolution

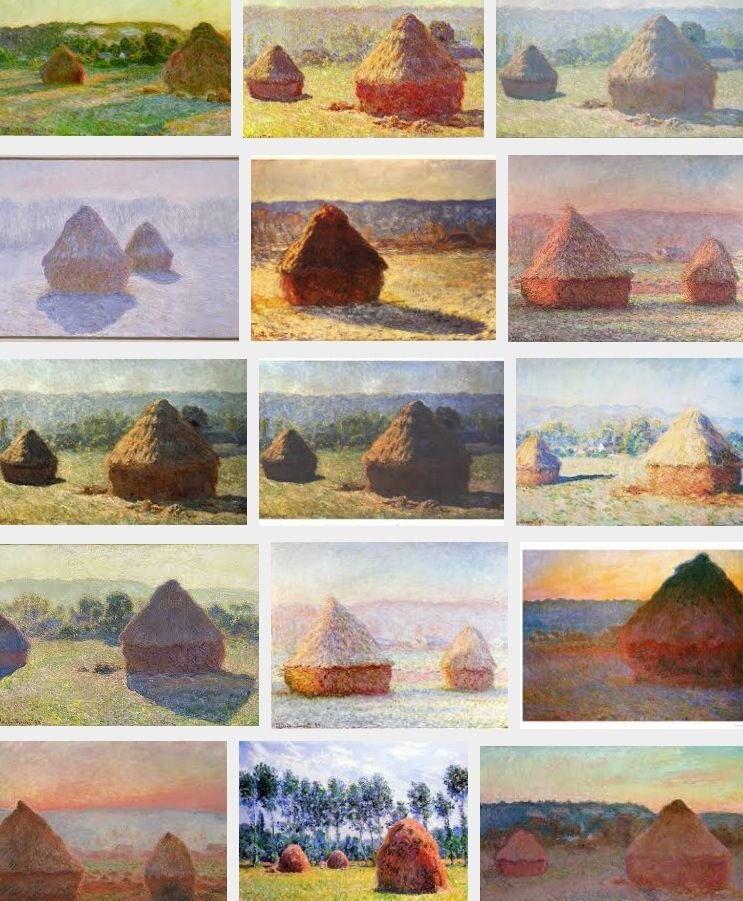

Over time, this interplay of taste and art leads to cultural evolution. New art forms emerge, often initially appreciated by few, then gradually more, becoming part of the cultural repertoire. Culture, in a sense, “learns” and “adapts”. We saw this with modern art in the 20th century, for example: impressionism, then abstract art, then conceptual art. Each of those was considered shocking at first, then slowly integrated.

Now, even schoolchildren learn about Van Gogh’s once “radical” style. Each time taste evolves, it doesn’t fully discard the old but rather adds new dimensions. A person today might enjoy both a Renaissance painting and a piece of pixel art, our taste spans more dimensions than that of someone who lived before digital art existed.

And if a society cultivates taste, it tends to also cultivate empathy, since appreciating art often means empathizing with perspectives within it. It’s the case too for critical thinking, since complex art often challenges us to think and “solve” puzzles, as we’ve seen before. Moreover, a society with rich taste is likely to produce art that future generations find valuable, thus enriching human heritage.

Well-being and meaning

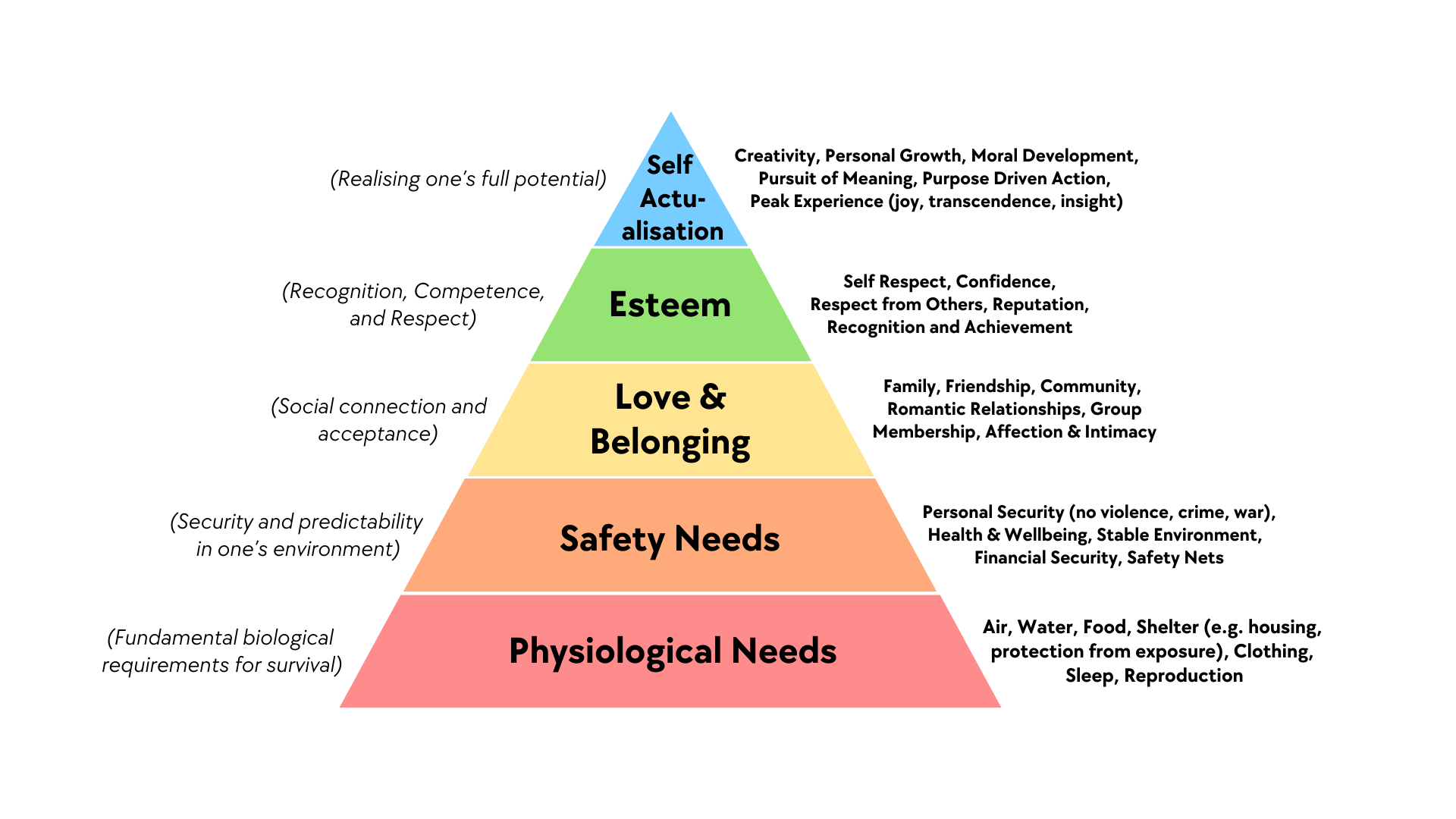

On a societal well-being level, refined taste and complex art matter because they fulfill higher aspects of human needs. Once basic needs are met, we then tend to seek meaning, self-actualization, and connection (as per Maslow’s hierarchy). And art often provides those. A society with only “shallow” entertainment might satisfy amusement but leave a void in meaning.

Aesthetic experiences are linked with emotional regulation and psychological flourishing, proving that beauty itself can play a role in well-being (Mastandrea et al., 2019). Architecture studies also indicate that perceptions of beauty in built environments influence well-being and behavior (Coburn, 2019). But we don’t need studies to tell us that a beautiful world is more pleasant than an ugly one.

Going even beyond that, ideas from the Symmetry Theory of Valence and neural annealing hint at why art might be transformative: the aesthetic experience could be a pathway to altered states of consciousness. The notion of “neural annealing” suggests that intense experiences let the brain enter high-entropy states and then settle into harmonious states (insight, peace…). This applies to how a great piece of music can first shake you and then resolve, leaving you in a “cathartic” state. If this is true, art is not a luxury but a way to re-shape your mind, so it’s no wonder that people through the ages have considered art quasi-sacred or transformative.

Why “better” art matters

It’s commonly tricky to call one art “better” than another objectively. But within our framework, we can define “better” art as art that creates more lasting, layered, and shared positive experience: more valence in the STV sense, across more dimensions.

By that definition, a symphony might be “better” than a ringtone because it can make us feel more and think more, and remain interesting after many listens. It can appeal to our primal sense of rhythm and harmony, but also play cleverly on familiar melodies, break a few rules, introduce a complex emotional story (based on the composer’s own life), etc.

If we accept that some art can be more profound, then encouraging the production and appreciation of such art seems valuable. It literally enriches lives.

Think of personal moments: reading a great novel that changed how you see the world, or hearing a song that became the soundtrack of a decade of your life. These are worth taking seriously. And when taste is ”improved”, those experiences become more likely and frequent.

Additionally, an ecosystem of refined taste can preserve important truths and feelings in art that might be lost if culture only chased immediate likes. Art can also challenge societal flaws (satire, dystopian art, etc.), and an audience with a taste for nuance will be better equipped to absorb and act on those messages than one that just wants escapism.

In summary, refined taste matters because it amplifies human experience. It allows us to ascend from base pleasures to more sublime ones, and it propels the arts forward, ensuring that we don’t just recycle the same cultural products but continue to create new ones that speak to the rich complexity of human life.

Conclusion

We have outlined a unified theory of taste that bridges biology, cognition, consciousness, and social psychology. Centrally, its claim is that taste is neither purely subjective nor strictly objective, but a dynamic relationship between human minds and artistic patterns.

Durability across repeated exposures and across centuries is one of the clearest signs that some art resonates more deeply. Works that survive when their original context has faded offer evidence that taste has intersubjective dimensions. The Mona Lisa was painted five centuries ago, and we’ve seen her face everywhere, yet it still leaves us filled with wonder and mystery. Thus, survival and relevance of art through time can give us precious clues about what properties “good art” must have.

On the biological side, our brains come pre-equipped with certain preferences: symmetry, harmony, familiar forms, etc, that bias what we find beautiful. On the cognitive side, we are active interpreters and predictors, finding joy in puzzles solved and expectations violated. On the social side, we learn from others what to appreciate, gain deeper pleasure through context, and sometimes confuse genuine liking with social signaling.

And far from making taste arbitrary, these layers create a framework that explains why so much convergence in taste exists amid personal differences.

But if that’s the case, and looking back at the introduction, why does it so often feel like people prefer uglier things today? The short answer is: they don’t, at least not directly. But the higher layers of taste are easy to hijack.

First, status games don’t reward beauty. They reward being one step ahead of everyone else. When the “cool kids” like something, it spreads to the “less cool kids,” then the “trying-too-hard kids,” and finally the “not cool” ones. By then, the initial trendsetters have already moved on to something intentionally weird or previously considered trash, just to stay different. And the cycle repeats. This sadly decouples social reward from liking good things, and taste just becomes a cynical signal of ingroup membership.

Second, modern production optimizes for efficiency, not beauty. When we cut costs, we tend to also remove any superfluous craftsmanship, which is often where depth can be found. Modern construction prioritizes code compliance and cost per square foot over our aesthetic response. Tiny margins compound this, because when failure is expensive, it’s better to retreat to proven formulas (sequels, reboots, pop formulas…). The result is the homogenization documented earlier, where variety and complexity declined as production became centralized and risk-averse.

This isn’t to say efficiency has no place. It’s better to house thousands of people in ugly buildings than to spend decades building one beautiful palace. But I think the choice isn’t binary. Vienna’s social housing from the 1920s provided affordable apartments with courtyards, decorative facades, etc. at a massive scale (and that was a hundred years ago, surely we have better tech today). We’ve simply stopped trying, accepting ugliness as inevitable when really it’s the result of optimizing for cost alone while ignoring long-term value.

Third, the attention economy prevents the cognitive work required for refined taste. As you know now, developing aesthetic appreciation requires repeated exposure: each encounter with a work lets us discover new patterns and build richer mental models. But modern media is like a slot machine of novelty optimizing for instant engagement. Algorithms promote what grabs attention in ten seconds while burying complexity that requires more patience. It’s so easy to skip a song and never listen to it again, so we never get the exposure needed to move from “confusing” to “interesting”.

More subtly, this trains our brains to expect immediate payoff. When every swipe delivers something new and every scroll promises a quick dopamine fix, the cognitive capacity required to sit with complexity weakens. This constant shallow stimulation keeps us too distracted to find depth, leaving us functionally stuck at lower, more easily satisfied levels of taste, but the higher levels are never touched and annealing can’t happen.

Fourth, and maybe more controversially, we’ve lost our shared reasons to make things beautiful. For centuries, beauty was often a collective offering: to God(s), to progress, to the future… When we lose the beliefs necessary to inspire multi-generational projects (like a cathedral that takes 500 years to build), the incentive to create lasting beauty collapses. Today, most of our grand narratives have fractured. God is dead, the future feels uncertain, and optimism sounds naïve. And in a fragmented world, it’s hard to agree on what’s worth glorifying, nevermind work together to build it.

But this erosion is not inevitable. Importantly, our theory argues that taste can be cultivated. This happens through exposure to complex art, environments of beauty, silence, and patience. The more we practice attending to harmony and subtlety, the more we can strengthen those attractor states. Cultivating taste, in this context, is not so much “elitism” as rehabilitation.

This way, both individuals and societies can ascend to more refined pleasures. And with refinement, our world becomes larger and more vibrant. If we care about the well-being of society, we should care about its aesthetic health too.